Thursday, August 2, 2007

Posts Welcome

Wednesday, April 18, 2007

Welcome

This interactive website was created in 2007 by the Best Practices Subcommittee of the Virginia Alliance of Social Work Practitioners and the League of Social Services Adult Service Committee. This website/blog exists to capture and share the excellent work being accomplished every day by adult services and adult protective services professionals across the Commonwealth in service to disabled, vulnerable adults 18 and over.

Since 1976 in the Commonwealth of Virginia, local departments of social or human services have been mandated to provide adult services and adult protective services. The statewide Department of Social Services (DSS) has given each jurisdiction local control to develop their own methods of practice, administrative systems, and supportive tools to do their work.

The result has been a rich diversity in how “locals” carry out our mandates. Daily, as professionals in each jurisdiction, we often grapple with how to do the right thing at the right time in the right way for our clients. The authors of this website interact daily with clients, their families and citizens of one of the 119 local jurisdictions.

The information on this site comes from trial and error, common sense experience gathered from over 30 years of experience in Adult Services work, as well as a review of the limited research within the field of Adult Services in Virginia, North Carolina, New York, Massachusetts, and other states.

Our experience leads us to believe that we locals have much more in common with each other than we have differences. We are hopeful that you will find this on this site to be a practical, helpful place to have a conversation about how to carry out our missions to the best of our abilities.

We strongly encourage you to post any thoughts you have surrounding the issues discussed. So please share by clicking "new post" in the dark blue toolbar at the very top of this site. Please identify yourself by name and jurisdiction when doing so. Constructive comments will be added to the body of this blog. Thank you for your time in reading and responding to this material.

VA Guidelines for Excellence in Adult Services

The Goals of this Site

- 1. To provide a forum for the 625 Virginia Adult Services and Adult Protective service frontline workers and supervisors to share how they have best met clients' needs. Please note: Any form on this site can be sent to you by mail, e-mail or fax by using the "new post" function and making this request

- 2. To optimize outcomes for adult clients and their families by describing and sharing excellent social work practice and effective supervision

- 3. To define a body of values, knowledge, and skills essential to social work practice with vulnerable adults

- 4. To identify and seek to remove or reduce barriers to excellent practice

- 5. To identify how frontline workers, supervisors, administrators, and those at the state level must work together to achieve excellence

Information on this Site

- Welcome

- Virginia Guidelines for Excellence

- Goals of this Site

- Information on this Site

- Need for Misson and Vision Statements

- Intake

- Frontline Workers: Perspectives/Traits that Lead to Excellence

- Frontline Workers: Assessment Beyond the UAI

- Frontline Workers: Counseling

- Frontline Workers: Case Management

- Frontline Workers: Limit Setting with Clients/Family - Case Example

- Frontline Workers: Time Management

- Frontline Workers: Working With Family and Informal Supports

- Working With Companions/Home-Health Aides

- Determining Companion/Homecare Hours Other Jurisdictions Use - Pages 1-8

- Supervisors Role

- Supervisors Role: Creating Depth of Supervision/Case Conferencing

- Supervisors Role: Limit Setting

- Supervisor's Role: Keeping Workers Safe in the Field

- Supervisors Role: Caseload Size as a Barrier to Excellence

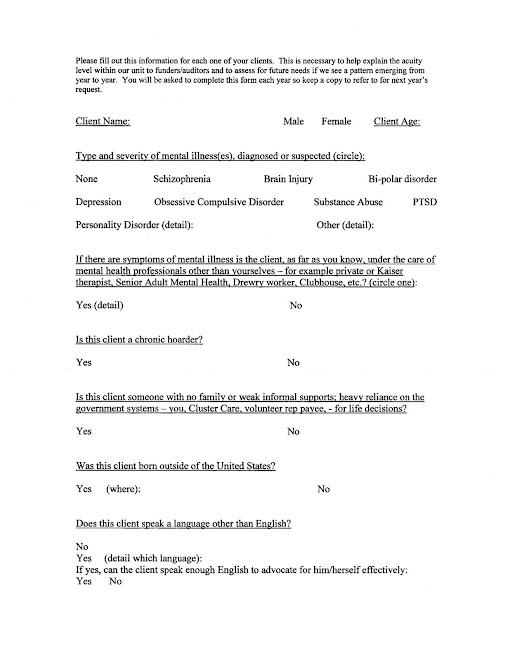

- Explaining Acuity Levels Within Caseloads - One Jurisdiction's Form

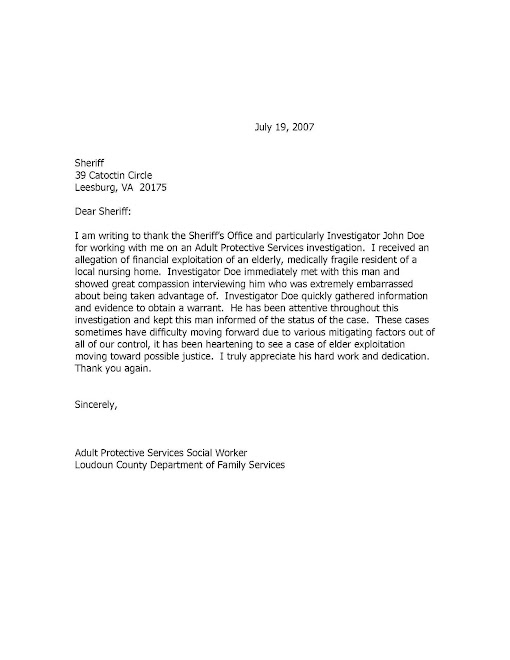

- Supervisors - How to Celebrate and Communicate Frontline Workers Successes - Story One, Story Two, Story Three, Story Four

- Need For MultiDisciplinary Teams

- On Going Training, Mentoring, Professional Associations

- Record Keeping: Importance Beyond Data Gathering

- Evaluations

- Other Available Assessment Tools Other States Use

- Research: Books and Articles

- Helpful Links

Need for Mission and Vision Statements

- Lacking a mission statement, organizations and their employees inside and outside adult services make the mistake of assuming what we do, rather than understanding the purpose. Clear guidelines about what you do for whom and how, which should be one of the by-products of a well-formulated mission statement, help the agency direct resources where they will do the most good. Without clear guidelines regarding access to the agency, programs become reactive, because they are defined by those who seek services rather than defining for themselves which clients they can best serve.

- Local jurisdictions may wish to take into consideration the federal goals of Title XX of the Social Security Act Amendments of 1974 and the mission and philosophy statements given by Virginia DSS when crafting the adult services mission statement of your local agency.

- A note in particular about serving adults ages 18 to 59: Although at the national level, via the Older Americans Act, Social Security Act and Medicare, there has been attention given to public social services for older adults, less is available concerning younger disabled adults. These clients have clear needs but no specialized agency to address them. This may be because the public policymakers hold deep-seated assumptions that adults in this age group should be independent. Additionally, because of the diversity of needs and interests within this group, these adults have no ready focus around which to assemble advocacy groups.

- A mission statement is ideally a one- or two-sentence statement that addresses five basic questions:

- This results in overlapping responsibilities to these clients among public social services and other segments of the health and human services community. Services for clients with persistent mental disorders are a prime example. Although mental health programs are available to people who have mental illnesses, a typical adult services caseload will frequently include substantial numbers of clients who have mental illness but either lack insight that they need mental health treatment or cannot physically get to the Community Services Board or Behavior Health offices. In these cases espcially, it is crucial for administrators to have a strong and clear mission statement as well as written criteria spelling out with clear guidelines which clients adult services workers are to serve.

- 1) Who are we as an organization or how do we fit in the larger human services organization in which we work?

- 2) What are the basic social needs we exist to fill or social problems we exist to address?

- 3) What must we do to recognize or anticipate and respond to these needs or problems?

- 4) What are our core values and how do we function in order to adhere to those values (clients rights as well as customer service as well as performing as public servants responsible to a larger community)?

- 5) What makes us unique and distinctive (what is it only we do)?

- Example: Arlington County's Mission Statement is: "Arlington will be a diverse and inclusive world-class urban community with secure, attractive residential and commercial neighborhoods where people unite to form a caring, learning, participating, sustainable community in which each person is important." Arlington Department of Human Services Mission: "We are committed to maintaining a healthy, stable, and safe community by focusing on prevention and promoting independence and self-sufficiency." Adult Services Mission Statement, Arlington County: "The mission of Adult Services is to provide community-based care management services to homebound adults over age 18 with physical, developmental and/or psychiatric disabilities who are unable to effectively advocate for themselves with the goal of preventing or treating abuse, neglect or exploitation and limiting premature institutionalization so these at-risk clients may remain an integral part of Arlington County’s diverse, inclusive, caring community."

- Please consider sharing your mission or vision statement by clicking "new post" on the toolbar at the top of this site.

Intake

- Intake is so challenging and requires such a diverse set of abilities, agencies should consider putting some of their most experienced and talented workers in these positions.

- The circumstances under which clients make contact with the agency deserve close attention, as does the professional training of the personnel whose responsibility it is to begin the relationship with clients.

- The successful intake worker must be someone with a knack for getting a brief account of the client’s desire for change, who enjoys being a generalist and knowing about the programs and services offered at the agency and in the community, and who is satisfied with and finds meaning in offering short-term services.

- An intake worker needs to be skilled at risk assessment for the elderly and disabled population

- The excellent intake worker hears the person’s story without making judgmental statements; tries not to be defensive when confronted with angry or hostile clients and diffuses negative emotions by acknowledging their validity. The greatest service a social worker can offer in the initial contact is to quietly listen, hear and enter into the world of the client. When clients are not self-referred, immediate questions arise about their knowledge or view of a situation and the need to involve them as quickly as possible.

- The intake worker should be aware of services outside their own agency as well as inside.

- As gatekeepers, it is the excellent intake worker who forms collegial informal working relationships with their peers in the service community and who often overcomes many of the barriers to access that clients encounter.

- In examining the coordination of community-based services for older adults in a number of Alabama counties, Bolland and Wilson (1991) found that much of the universally decried service fragmentation was overcome by the informal networking of service providers.

- Formal agreements negotiated by the adult services supervisor as well as screening guidelines established among service providers can lighten the intake worker’s task.

Frontline Workers - Assessment Beyond the UAI

- For it’s purpose as a state-wide multi-dimensional screening tool, the Uniform Assessment Instrument is excellent. However, there are many factors beyond the UAI that should be considered by the excellent frontline worker when crafting a plan of care, such as:

- Client's prior occupations and avocations

- Family traditions that keep client strong and stable over time

- Ethnic customs and dietary habits, attitudes toward the roles of adult children, and other cultural issues

- Life cycle experiences associated with work, marriage, child rearing, and illness that resulted in various positive coping skills and adaptive strengths

- Research shows the presence of just one person the client considers a “confidant” has been determined to be the single-most important factor for personal well-being (Antonucci, 1985). To assess the depth of an individual’s social support network questions should address not only whom the client can call on for support but also for how long and in what circumstances.

- Economic assessment should involve looking beyond income and assets to understanding clients’ values and abilities concerning spending (or refusing to spend) money.

- Mental health: Social workers should be familiar with symptoms and manifestations of the major affective disorders.

Frontline Workers - Perspectives and Traits that lead to Excellent Work

- Best practices dictates that it is important to see adult services clients as individuals with independent lives, interests, families and histories outside of their involvement with the program. Practitioners should acknowledge and personalize their clients’ histories, celebrate their achievements in the face of obstacles and, absent significant cognitive impairment, confirm their right to control their own destinies.

- Traits excellent frontline bring with them to the job:

- A capacity for empathy

- An ability to assess functionality accurately and communicate both strengths and weaknesses of clients to others

- Readiness to be flexible in response to the client’s changing needs.

- Ability to tolerate uncertainty and remaining risk often present in community-based work

- Ability to adapt to a wide range of settings, life styles, cultures

- Ability to work as a team member

- Ability to make independent judgements/decisions

- High tolerance for frustration and never-ending nature of the work

- Confidence; imagination; sense of humor

- Articulate in making prepared as well as extemporaneous talks

- Willingness to learn and follow agency policies, procedures

- Non-judgmental; persistent

- Ability to prioritize

- Self-awareness and professional objectivity

- Ability to remain calm and focused in crisis situations

- A willingness to stand up to others involved with the client to support the client choice and client's remaining abilities

- As clear an understanding of what is not their job/role as well as what is

Frontline Workers - Counseling

- Rothman (1991) made a useful distinction between counseling and therapy. He characterized counseling as an approach that is not as highly intrapsychic as traditional therapy, but which does deal with internal beliefs and concerns associated with change, reality testing, socialization skills, and accepting practical help.

- For some clients the greatest need is to use internal psychological resources they have developed over years of living so they can make the best use of tangible resources. They often must feel the consequences of their decisions in order to achieve the necessary motivation to change behavior, cope with losses, regain skills they have forgotten. Counseling in adult services is an intervention strategy to help clients manage their internal psychological resources effectively.

- The investment in training AS workers in counseling is well-worth the agency’s effort. If clients are unable to use the agency’s material resources well because of problems in emotional functioning, those resources are wasted.

- In counseling clients, adult services social workers do not attempt to identify or deal with the remote, historical origins of a problem except as they currently have a bearing on the efforts to improve functioning. They do not engage in long-term therapy.

- Counseling is purposeful communication and dialogue with clients and families about change. It is performed in the context of a respectful, genuine and empathetic relationship. The medium by which this dialogue is initiated and maintained is through in-depth conversations about change between worker and client. The goal is to empower clients and families by helping them find ways to change thoughts, feelings, attitudes, and behaviors that interfere with their abilities to meet their goals or to use resources in ways that would enable them to function optimally.

- In ensuring social workers gain skills in counseling, they and their supervisors should seek out trainings specific to the needs of their workers.

- Although often these trainings are geared towards office sessions, for Adult Services workers counseling is more likely to take place in the client’s home. This location provides both opportunities and challenges. Clients may be more receptive to counseling on their own territory and more comfortable sharing personal information. The social worker’s understanding of clients is usually deepened by seeing them in their own environment. On the other hand, the worker has less control over those environments: Family and friends may walk through the room, the telephone may ring, etc. The social worker must find ways to minimize distractions and ensure privacy.

- Another unique consideration for counseling in Adult Services concerns its opportunistic nature; often consisting of brief conversations during home visits, telephone calls, or when providing transportation. Counseling in this manner is no less important because it happens on the fly, capturing openings for constructive dialogue and providing supportive assurances as the opportunities arise.

- The type and quality of relationships between social workers and clients will depend largely on the communication skills, purpose and values of the worker. The purposive nature of the professional relationship is important. Workers, for example, who describe their roles as the “client’s best friend” risk losing their objectivity, promoting inappropriate dependency in clients, and compromising the function of the agency.

- Social workers in AS are not and should not be the principal providers of mental health services in the community. However, they can offer a valuable source of support to clients whose need for change is complicated by emotional and psychological issues. Social workers performing this service must be self-aware; must exhibit an emotional maturity when assisting others in managing their emotions; listen to clients on a deeper level; and provide constructive feedback.

- Social workers and other staff members who have contact with clients must be aware of their own values, tolerances and intolerances. They must know their “buttons” and what pushes them. Some people react strongly to profanity, whereas other do not. Some staff members are sensitive to clients’ criticism of their work, whereas others take it in stride. Increasing self-awareness allows workers to identify their own automatic responses and prepare more appropriate ways of acting.

- For example if cursing is offensive to a particular Adult Services worker, she can have prepared a way to handle this by saying: “I find it hard to listen carefully when you use those words.”

- If the social worker does not recognize and deal with personal negative feelings, they may come out in unintended ways – not acting as quickly on clients’ requests, not taking complete action, or not advocating as strongly for these clients. Self-awareness also helps social workers set reasonable, rather than punitive, limits with clients. Examining these issues in the course of supervision helps workers discover the effects specific behaviors have on them.

- If the worker can say (and feel) that “Mr. Jones is very persistent about getting his needs met and anxious to change his situation” rather than “Mr. Jones is manipulative and is driving me crazy with his frequent calling,” he or she may be able to respond to the client’s anxiety and defuse it some.

- Whenever a client expresses ambivalence, rejection or fear, the AS worker must slow down, back up and identify the specific cause. Expression of negatives should be encouraged. The client should have an opportunity to sleep on the discussion before committing her or himself to further action

- Potentially useful questions:

- Tell me about . . . .(your typical day)?

- Help me understand . . . (how it is with your son living with you)?

- How was it when . . . (husband died, WWII, etc.)?

- Have you ever felt this way before? How did you handle?

- Future thinking: “What would you most like to happen?” Or “What is the worst thing that could happen?”

- Goals and the means of achieving them are never reached unilaterally. Except in extreme circumstances, a client is capable of some degree of involvement. AS workers must never forget it is the client who must live out the consequences of any actions taken. Sharing of the case plan and its implementation is an ongoing process, requiring repetition, simplification, and clarification at each stage.

- A distraction free, well lit environment is necessary. The worker should position himself or herself before the client, facing the light to facilitate lip reading. Smoking, gum chewing, eating or hand gestures that cover the mouth are to be avoided. Care must be taken to speak clearly, but raising one’s voice is usually not helpful and perceived as patronizing. Speaking a little slower than usual can help with the client who needs time to sort out sound.

Frontline Workers - Case Management

- What brings clients to the attention of adult services is often the need for tangible resources: a better or safer place to live, help with personal care, a financial need. Case management is the intervention strategy social workers use to obtain and coordinate these external, tangible resources for clients.

- The resolution of clients’ problems often lies in:

- 1) optimizing the fit between the person and his or her environment by addressing clients’ dysfunctional beliefs and/or changing or modifying the actual physical environment

- 2) tapping their internal resources and strengths

- 3) helping them gain access to needed resources

- In helping clients access services, social workers are guided by agency policy and professional training. Both are important because the complex nature of adult services cases not only allows but calls for considerable administrative and professional discretion with respect to allocating agency resources, identifying and overcoming barriers in the service system, and identifying new resources and services that must be developed in the community.

- If the client only wants to continue to receive outside emotional support, because of the agency’s mission and the constraints on the worker’s time, the worker will likely need to find other ways to arrange for this support, through facilitating the client’s relationships with family members, neighbors, friends, church groups, volunteers, senior centers, etc. Although the client’s need and desire for support are legitimate, it is a better use of professional resources for the social worker to arrange for someone else to provide it. To be avoided are situations where the client’s dependence on concrete services is perpetuated only in order to maintain a social contact with the AS worker.

Idea on How to Strengthen Working Relationships within Jurisdictions

Frontline Workers - Limit Setting with Clients/Families - Case Example

- Mr. S calls his social worker almost every day to talk about minor complaints and problems. Once Mr. S has the worker on the phone, he usually keeps her occupied for 20 to 30 minutes. In the context of his situation and her busy caseload, she decides that two phone calls a month is all she can accept from him.

- Mr. S does not agree that limiting his contact to two phone calls is adequate. She tells him she understands he would like to talk more frequently but because of her responsibilities to other clients she cannot spend so much time on the phone with him.

- However, she asks him to choose which days and at what time he would like her to call, during which time she is careful to listen attentively and with empathy.

- During one of their conversations, she helps him develop strategies for meeting his need for contact and puts him in touch with a telephone reassurance program.

- During the first month of the new plan, Mr. S calls her to test the new limits. The worker reminds him of the new plan and tells him that in the future she will hang up if he calls, except in case of immediate emergency.

- When he calls the next week, she finds out briefly the reason for his call (not an emergency) and says, "I cannot talk with you now, Mr. S. There is no emergency. I will talk with you at our next scheduled date, Tuesday. Good-bye," and hangs up.

Frontline Workers - Time Management

- How is the social worker to cope with large caseloads and still practice skillfully with clients in need? The answer is not an easy one, but some steps can be taken. They are related, first, to handling personal reactions and, second, to organization of the workload.

- The time devoted to direct practice must be rationally allocated based on the worker’s assessment of who need immediate attention and who, given calm reassurance, can wait. Often a brief supportive phone call with anxious clients will suffice.

- As part of best practices, with some clients social workers must set limits on agency resources and on their own time. This must be done sensitively and fairly but in a matter-of-fact way, such as described above.

- The worker who begins with an open door, equally responsive to all client demands, willing to give up lunch hours, or work overtime in order to see everyone, will not last long.

- Other professionals and informal supports in clients’ lives often call AS workers with their own plans of care (what they want AS workers to do) and want you to implement them. What a social worker is expected to do with clients is different in each citizen, family or client’s mind. This often results in unreasonable demands on an adult services social worker. What a worker can control is his or her reaction to these (often daily) unreasonable demands:

- An excellent AS worker listens to such demands without an emotional reaction but does respond to the concern being expressed, gathers the facts without the agenda of the caller and asks him or herself: "Is what I'm being asked to do appropriate? Am I really needed here?"

- A key lies in apportioning a certain amount of time to each set of tasks and within each category and setting priorities. This division of labor needs to be shared with others so that effective feedback loops are in place informing management of the real needs that exist but are not met.

- Adult Services workers can often monitor their clients through telephone contacts, by talking with service providers and, others involved with the client. Quarterly contacts are mandated.

- Reassessment requires more extensive contact with the client and family, focusing specifically on change since the first meeting. The reassessment provides the opportunity to look again at the client’s and family’s situation as if for the first time. When social workers have seen clients for over 2 years, it is possible for them to develop a fixed view of clients and their various problems. Stepping back to view the case with detachment may make it possible to see issues and strengths that have not yet been identified or to reevaluate the situation in new and constructive ways. This also allows the social worker, client, and family to review whether the agency’s services still match the client’s needs. The re-assessment UAI mirrors the original in the comprehensiveness of its review of the domains, but it focuses on reviewing the change thus far accomplished and identifying if future change is desired and if the AS worker is a necessary player in that change.

- Preparation for going on a home visit to see a new client is generally recognized as essential. Less recognized is the need for worker preparation before each reassessment home visit, no matter how long, or well, the client is known. This is especially crucial to review notes, UAIs, other paperwork when seeing a client who has been with the agency for many years. This is especially crucial when caseloads are large and clients seen less frequently. Minutes spent on preparation are amply repaid in efficiency.

- Even with the most experienced, able and committed workers, doubts are never laid completely to rest. What characterizes their ability to function so well is the perspective in which they are able to place their work. They recognize that the success of practice need not be measured by great changes accomplished but rather by small increments.

Frontline Workers - Working With Family and Informal Supports

- While family involvement with frail clients is extensive, it is also widely diverse. There are no laws or specific contracts that govern the behavior between adult family members with the exception of the marital relationship. Furthermore, there are no universally accepted norms of filial responsibility. While adults are expected to act responsibly toward their aging parents, they may fulfill this responsibility in varying ways and degrees.

- There are also varying ways in which clients relate to their extended families. Some clients are deeply embedded in the family structure; others are not. While many elders turn to their families at times of crisis and expect the family to be dependable, often those who come to the attention of adult services and adult protective services are those who have no or little or negative family interaction, therefore relying more heavily on workers and hired helpers to remain in the community and may expect the adult services worker to be a surrogate family member.

- When the client’s needs and preferences come into conflict with the family's it is the client's needs and preferences that are most important in creating a service plan. However, the excellent social worker offers counseling, mediation, and education to enable the client and family members to reach the most acceptable solutions.

- Some Roadblocks to Effective Problem Solving when working with families:

- Keeping Secrets - They are undertaken usually under the guise of protecting “my children” or protecting “mother.” Usually, however, they are undertaken to protect oneself. The keeping of secrets hinders the problem solving and allows for unhealthy manipulation – workers should attempt to avoid being unwitting players in a family’s unhealthy dynamics.

- Claims by adult children that siblings live too far away or are disinterested should never be taken at face value. Omissions from the family decision-making process of a close member are to be avoided. The worker should make every attempt to gain consent from the client to speak with family members or friends who express concern, who will be affected by the decision to be made, or who have resources to offer, even if a third party claims “he’s not interested.”

- Often there are more supports than clients report initially. Sometimes relatives and neighbors who have dropped out of the picture can be re-engaged if responsibility for the frail client is shared and they are assisted by the expertise and backup of the social worker.

- Friends and neighbors willing to help a mentally impaired client need a very special type of support from the worker as the client may offer few gratifications.

- It is important that whatever help the family friends offer be specific and realistic. It is the worker’s role to encourage realistic contributions from family members and avoid pushing them beyond their capacities. Family members may have personal shortcomings and display less filial devotion than ideal but Adult Services workers should attempt to interact with them without judgment.

Working with Companions/Home-Health Aides

- When working with companions or aides, it is often the adult services worker’s role to define what a companion/aide is to do for a client. An excellent AS worker communicates an explicit plan for the in-home aide’s services to prevent misunderstandings about the aide’s obligations and duties. A careful assessment of the aide’s skills and preferences in light of the client’s needs and preferences can help ensure quality services. Although it is not possible in all situations, many social workers try to match clients and aides as carefully as possible.

- A close social work involvement should follow the initial contact of client and helper, especially crucial if the client is a first time consumer of home care services. A follow-up conference to review the service and identify incipient problem areas should be held as soon as feasible. The structure of the conference established that client and helper are to communicate directly rather than waiting for time alone with the social worker to pour out grievances. The problem-solving approach demonstrated by the social worker during the meeting provides a model for the client and helper as they strive to accommodate to each other’s ways.

- Any difficulties of the first few days should be brought into the open. A nonjudgmental exploration of the facts is in order. Client and helper should be encouraged to express their views of the situation to each other, focusing on issues rather than personalities. Whenever possible, a future approach to the problem can be discussed. Increased responsibility on both sides foster a shared ownership of the problem and investment in a satisfactory resolution.

- The clearer the social worker is as to why the match failed the better able she will be to anticipate and head off future problems. Where family or significant others exist, it is important that the social worker reach out as necessary to interpret and clarify the home care worker’s role.

- Good supervision of in-home aides fulfills several functions:

- 1) Preparing aides for new clients

- 2) Monitoring the quality of their work – ensuring clients’ needs are met

- 3) Providing them with information and emotional backup when crises arise

- 4) Coordinating the requests of several professionals into a coherent work plan

- 5) Building on aides’ observations to understand the needs of clients.

- If clients have problems that are likely to result in confusing, annoying, or alarming behavior, the aide needs to be particularly prepared, not only to anticipate the problems but armed (by the social worker) with some suggestions about what are and are not effective and acceptable ways to respond to them.

- Monitoring the aide’s work may not seem conducive to a team relationship, but it can be so. If it is understood that every team member’s work is subject to review (the social worker’s by an adult services supervisor, the registered nurse’s by a nursing supervisor, and the supervisor’s by other administrative personnel) and if this review is given constructively as a basis on which team members can enrich the lives of their clients, it will seem less like policing or “checking up on” the aide. Research shows that, in general, in-home workers perceive supervision as support, and they would like as much or more supervision than they receive.

- Preventative Planning: Even the best problem solving cannot prevent occasional times when the aide cannot perform the expected services at the expected time. For these situations, the social worker client and family, if there is one, need to develop a contingency plan. Aide should have a copy of the contingency plans and one in the record.

- The relationship between the in-home aide and the client requires a delicate balance, perhaps even more difficult to maintain than that between social worker and client. A certain sense of intimacy is almost unavoidable, especially if the aide is involved in providing personal care. In fact the opportunity to develop close personal relationships is one of the most attractive and rewarding parts of the job of companion/aide.

- Kaye (1986) found that “even the most concrete of home-delivered services are powerfully colored by client expectations for non-instrumental (i.e. affective/emotional) forms of aid,” a conclusion that experienced in-home services social workers can validate.

- In most cases, the client is unaccustomed to and uncomfortable with the role of employer, erring by being too authoritarian (thus alienating the helper) or too passive (unable to make simple requests). The helper is frequently of different ethnic origin than the client, a member of a group about whom the client may hold deeply entrenched biases and stereotypes. Above all, the helper intrudes on the daily routine of the client, which, however dysfunctional, is cherished for its familiarity. The helper brings his or her own regimen of care, as well as idiosyncratic ways of cleaning, putting food away, even closing a door. Whatever the type or duration of service, the client must adjust to forced intimacy with a stranger.

- The client’s personal clock and past style of functioning should be adhered to where possible. There is nothing sacrosanct about a bath on arising or dinner at midday. The client can and should maintain control over the remaining choices in his or her life.

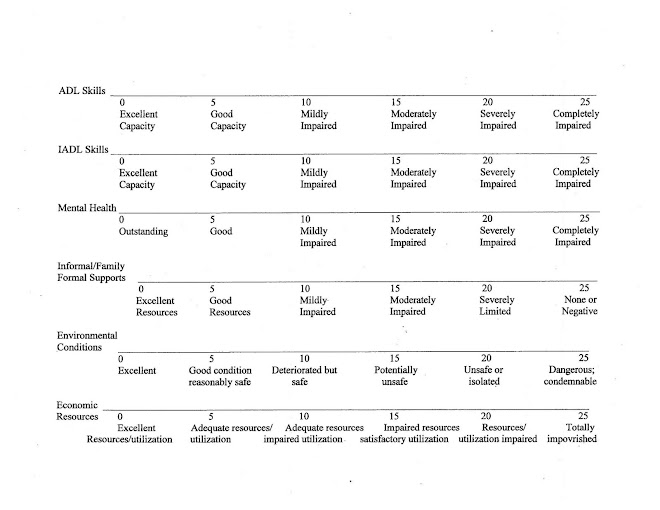

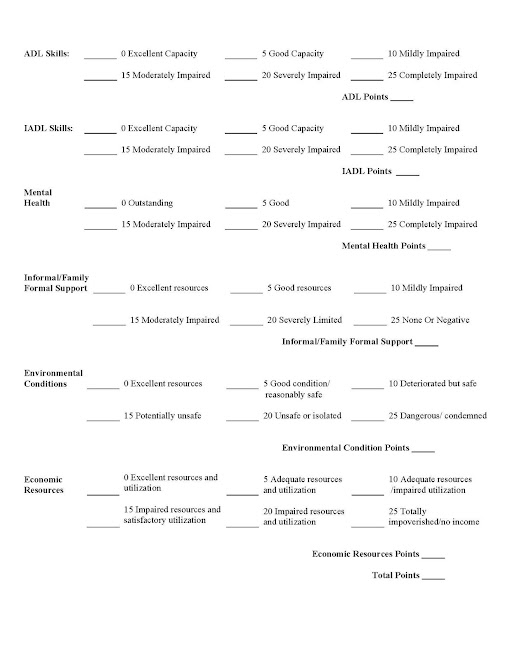

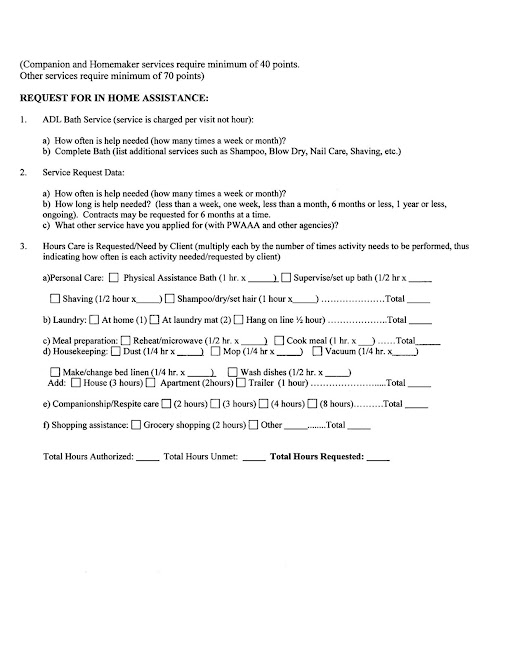

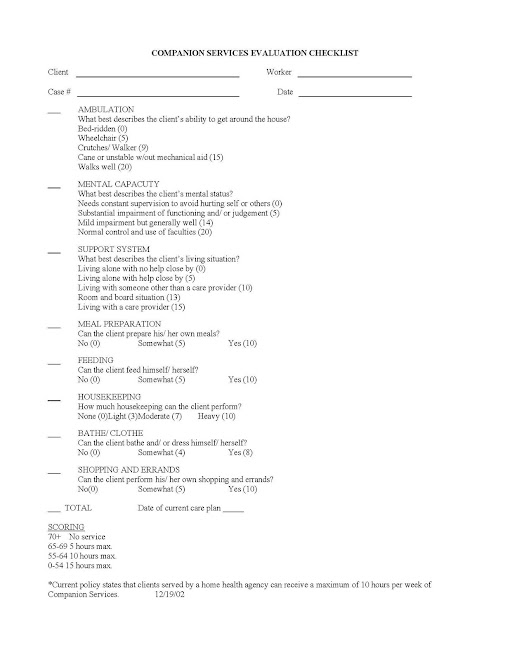

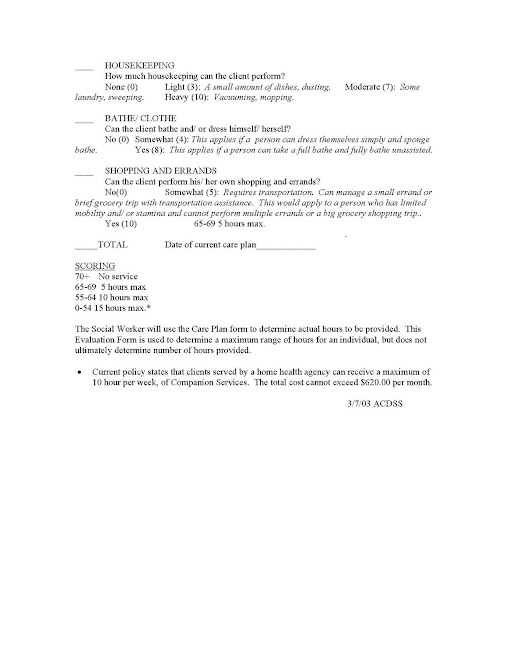

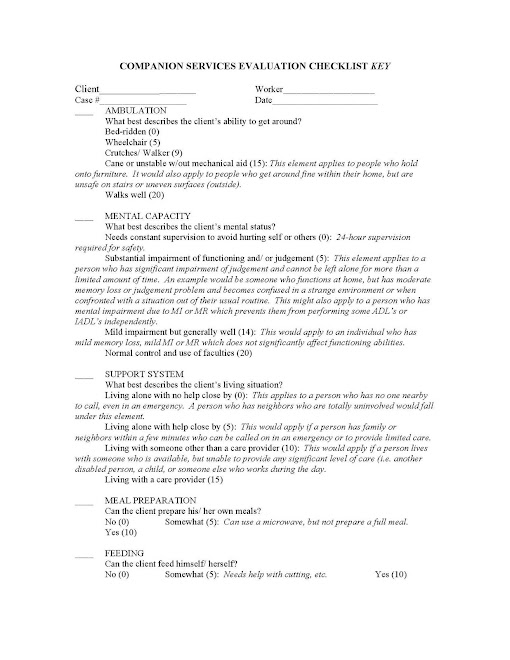

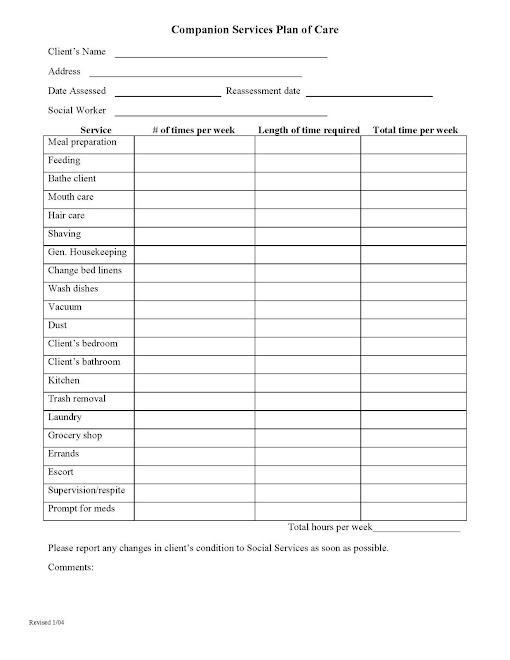

Determining Companion/Homecare Hours - Tools Other Jurisdictions Use Page 1

Determining Companion/Homecare Hours - Tools Other Jurisdictions Use Page 2

Determining Companion/Homecare Hours - Tools other Jurisdictions Use Page 3

Determining Companion/Homecare Hours - Tools Other Jurisdictions Use Page 4

Determining Companion/Homecare Hours - Tools Other Jurisdictions Use Page 5

Determining Companion/Homecare Hours - Other Jurisdiction's Tool - Page 6

Determining Companion/Homecare Hours - Tools Other Jurisdictions Use, Page 7

Tools Other Jurisdictions Use for Companion/Homecare Service Page 1

Tools Other Jurisdictions Use for Companion/Homecare Service Page 2

Tools Other Jurisdictions Use For Companion/Homecare Service Page 3

Tools Other Jurisdictions Use for Companion/Homecare Page 4

Supervisor's Role

- Fundamental to the notion of empowering adult clients is the manner in which administrators and social workers consciously or unconsciously view and treat people served by the program.

- We propose an underlying philosophy of empowerment to describe how best practices come to life in the day to day functions that make up adult services. Empowerment is necessary for clients and for their informal support systems as well as for adult services workers and their supervisors. An empowered environment is one in which mistakes are not seen as failures but rather as opportunities for feedback and improved mastery and competence.

- Excellent Adult Services Managers:

- 1) Understand the importance of developing a mission for adult services programs

- 2) Treat and respect employees at all levels as the key to quality services for adults

- 3) Determine and clearly communicate adult services job designs (key elements within a position as well as necessary credentials of staff)

- 4) Demonstrate a commitment to continuous learning

- 5) Determine how much it’s reasonable to expect people to do (workload)

- 6) Determine how well your workers are carrying out the stated mission (evaluation of quality, not solely quantity)

- 7) Determine what is a reasonable time frame for people to do what you want them to do (timeliness), in the amount you expect (quantity), and with the quality you want (best practices).

- 8) Honor and celebrate the success experienced by adult services staff members in serving their clients

- 9) Developing community resources and relationships that are beneficial to service delivery

- 10) Serving as a conduit and/or advocate with higher levels of agency management

- A NOTE CONCERNING NEW SUPERVISORS:

- New social work supervisors are generally promoted because they are very good social workers. They may have received no training in social work supervision. The personnel issues and the expectations of the social workers can be surprising to new social work supervisors. It can be difficult to sort out one’s role as a supervisor and there may be pressure to be a friend or a parent. Neither of those roles may actually be appropriate and may lead to dysfunctional office dynamics. Seeking out supervisory training is essential for new social work supervisors. Training curriculums should include: self assessment and a development plan; emotional intelligence; conducting performance evaluations; coaching of staff; high performance organizations; effective meetings; time management; effective communication; team development; cultural competence.

Supervisor's Role - Creating Depth Within Supervision

- Social workers’ relationships with clients require the need for support from social work supervisors. For example, social workers may experience: grief over the loss of clients; frustration over not being able to resolve clients’ situation; anger for how the client is treated by others; resentment of community, family members, and other agencies’ expectations about resolving the situation. Support may include focused listening to the social worker’s feelings about the client and the client’s situation and not offering answers.

- However, there can be too much attention given and too much support provided for the venting about the awfulness of situations. This venting can be normalized and part of the culture in social services’ agencies. Energy is drained from social workers and from supervisors when there is too much attention directed to the awfulness of situations. After the validation of the social worker’s feelings, facilitation of problem-solving with consideration of the client’s service plan is constructive.

- Problem-solving as a social work supervisor involves assisting the social worker with consideration of resources, the Virginia Code, state and local policies and procedures, and most importantly, what the client wants. No one likes to be given dictatorial answers – clients or social work supervisees. The real answers come from the social workers and ultimately from the clients. The social work supervisor is a skilled guide to possibilities.

- Supervisor’s Role – Structure

- Social work supervisors provide support by ensuring structure in the office. Structure includes: following through with commitments to meet; making sure that social workers know where/how to reach the supervisor; having regular meetings, and defined times for casework staffings; processing paperwork in a timely manner; being clear about expectations about paperwork, computer work, and field visits (see also creating depth within supervision).

- The social work supervisor also sets limits for the amount of work time. She ensures that social workers take time off from work when ill or for vacations and for training. The social work supervisor arranges for case coverage and/or provides coverage herself.

- Supervisors should consider instituting regular use of case staffings or unit meetings as places workers can confidentially share their frustrations and successes.

- Supervisors should support workers in dealing with emergencies by helping them identify appropriate resources quickly and by helping them keep a healthy perspective on who “owns” the emergency or crisis.

- Additionally, supervisors must enable and empower social workers by helping them prepare to act independently. This is part of the teaching function of supervision - to help social workers refine their skills and judgment and to support them in exercising professional discretion.

- Excellent managers create depth of supervision by:

- 1) Holding unit meetings

- 2) Being available to staff a case at times other than scheduled meeting times

- 3) Finding and sharing resource materials and allowing staff to do the same

- 4) Observing

- 5) Modeling behaviors

- 6) Holding individual supervisory conferences

- 7) Celebrating successes

Supervisor's Role - Limit Setting

- Clients who receive too little or too much care are not well served: Too little care and the client may suffer premature institutionalization, abuse, neglect, or even premature death. Too much care fosters dependence on publicly funded services, undermines the competence and the ability for self-care and weakens the family support system by supplanting it.

- Any worker’s success in interacting with “difficult” clients depends in great measure on the supervisor’s/agency’s support for setting limits, including clear guidelines, support and follow-through about consequences of inappropriate behavior.

- The social work supervisor may provide support by helping to establish expectations about client’s behavior. The social work supervisor also models the response to inappropriate behavior. Much inappropriate behavior can be managed with techniques of verbal redirecting or reflecting. Simple silence may be very appropriate and effective. For more disruptive or threatening behavior, more direct interventions may be needed.

- To set limits on clients’ behaviors may initially seem at odds with the notion of empowerment. However, limitations on behaviors can offer the disruptive client some insight into self-control and some training in how to get needs met in general. It helps preserve other clients’ access to the agency’s resources, specifically the social worker’s time. Some ideas:

- 1) Limiting such clients’ time with worker

- 2) Restricting their access to the building

- 3) Encouraging workers to press charges when they are threatened or assaulted

- It is important that consequences be enforceable and used consistently.

- Beyond this, supportive supervision or peer support, debriefing, time for ventilation, support of feelings, constructive problem-solving, can all help social workers manage the discomfort that confrontation with a client or other parties may trigger.

Supervisors - Keeping Workers Safe in the Field

- Supervisors can prioritize funds for cell phones for social workers even if phones are shared

- Within intake, supervisors can ensure safety-related information is asked and conveyed to the assigned social worker

- VISSTA offers a training on keeping workers safe in the field, which focuses on:

- Enhancing awareness of job-related personal safety issues and preventing personal harm.

- • Preventing, defusing, and dealing with threats

- • Structural and environmental hazards

- • Sources of potential danger, including animals

- • Personal safety plans and practical self-defense

- • Office and auto safety

- • Providing, at agency cost, items like gloves, hand sanitizer, pocket electronic whistles, and bug spray

- Many jurisdications partner with police officers in their localities to provide periodic worker training

- Others hire self-defense experts to conduct day-long trainings for staff

- How does your locality manage keeping workers safe? Please navigate to the top of this site, to the dark blue toolbar and click on "new post" to add your comments.

Supervisor's Role - in Identifying Caseload Size: A Barrier To Excellence

- In empowered programs, organizational leadership pulls others to excellence by example rather than by trying to push them through administrative directives.

- Studies of clinical effectiveness have demonstrated that a major determinant of effective practice lies in the quality of the relationship between social worker and client - 1994 p. 30. Knowing this, supervisors must ensure adult services workers’ workloads reflect the time necessary to develop the relationship as well as provide both counseling and care management.

- The demonstration of excellence is an evolving, continual learning process through which new methods are continuously proposed, adopted, evaluated and revised or refined

- Each jurisdiction is unique in it’s expectations of workers as outlined in it’s mission statement but with the increase in untreated mental illness within caseloads and explosion of requests for screenings for Medicaid services, consideration should be given to establishing realistic caseloads which would be beneficial to the client and to the quality of service they receive.

- Localities need to define what these numbers are, with significant input from the frontline worker as well as from a supervisor who understands the complexities of the workload for AS workers.

Explaining Acuity Levels Within Caseloads - One Jurisdiction's Form

Supervisors - How to Celebrate and Communicate Frontline Worker Successes - Story One

Flor Fiallos Preventing Financial Exploitation

On May 1, 2006 Flor Fiallos, adult services social worker, received a new referral - a terminally-ill cancer patient and his wife, Mr. and Mrs. H. Two weeks later the husband died, a major shock to his wife. She had relied on him to make all the financial decisions and it became clear to Flor Mrs. H had Alzheimer’s Disease with a severe short-term memory deficit.

There were no family members in the area. Mr. H.’s daughter from a previous marriage flew in from Puerto Rico. The stepdaughter stated she could not help with funeral expenses, however she requested Flor drop her and Mrs. H at a local Mall.

It became clear to Flor the stepdaughter was interested in spending the client’s small savings and that Mrs. H did not understand what was happening. In fact, Flor noticed that when Mrs H. tried to pull a white envelope out of her purse, the stepdaughter kept pushing the envelope out of Flor’s sight.

Flor asked Mrs. H to show her the envelope and found $1,400, which had most probably been hidden as cash in the apartment by the deceased husband. Flor immediately suggested, and the client agreed, to deposit the money. Flor went to the bank and asked the bank employee to put a hold on the savings account and alert Flor if there were any withdrawals, which he did.

The next home visit Flor made she found a neighbor who was “helping” the client “protect” more cash from the stepdaughter. The neighbor refused to answer detailed questions Flor asked about the amount of cash in the H’s apartment.

A week later Mrs. H’s sister came from Honduras and found $12,000 in cash in the apartment. The sister realized how forgetful client was and how easy it was for people to take advantage her. Flor educated the family that the only real option to them in this country would be nursing home, while in Honduras her Social Security check would be financially meaningful for an entire family, who could care for her.

Flor: helped with Social Security Office for transfer of benefits outside of USA, canceled Medicare, arranged for a complete physical, collected the client’s medical records from Kaiser, negotiated with a moving company to handle the move of the furniture to Honduras (door-to-door for $700.00), closed bank accounts, helped the two women buy airline tickets and wrote detailed instructions in Spanish to the cab driver to help the client and her sister get to the airport on July 13, 2006.

Since then, the client’s sister has called Flor to thank her for her work and let us know even though the client misses her life in Virginia, she keeps busy with young relatives, teaching them English and helping them with their homework.

CONGRATULATE FLOR ON PREVENTIVE SOCIAL WORK AT IT’S FINEST!!

Supervisors - How to Celebrate and Communicate Frontline Worker Successes - Story Two

Mrs. B., a 69-year-old widowed woman with a life-long history of mental illness came to the attention of Adult Protective Services in June of 2002, requesting financial assistance, all related to attempting to maintain the large single family home she lived in alone since the death of her husband a few years prior. APS worker Reginald L. worked with her for six months, advocating for client to receive funds from more multiple agencies in order to turn her heat back on, clear a tree on her property and more. Although he suggested she change her living situation (such as move to a HUD-funded senior building where her SSI check could support her), she refused to consider this option.

As this client was isolated and appeared to lack the executive functioning necessary to manage her house (but was not in sufficient enough risk to justify taking her to court to pursue guardianship), Reginald transferred Mrs. B to Allen Alexander. Allen worked with this client to establish rapport: taking her to physician’s appointments, obtaining funds from multiple sources multiple times to help her pay her basic bills, and, once she agree to it, making all the contacts with a lender necessary to attempt to obtain a reverse mortgage for Mrs. B. After one year of effort, the lender refused to give Mrs. B. the reverse mortgage due to “structural problems” with the home, which he refused to detail despite being given a signed consent.

Having exhausted all available public funds to pay her gas bill, Mrs. B.’s heat was cut off and she spent two winters without heat, using space heaters and an electric blanket and limiting her activities to one room in her home. Concerned about her continued inability to make executive decisions due to a long-standing mental illness, Allen referred Mrs. B to senior adult mental health for a capacity assessment. The result of the assessment was that client did not lack capacity and therefore could not be forced to have an alternative decision-maker appointed.

Allen continued to monitor client through home visits, regularly contacting her home health aide, and taking her to her doctors. Due to the temperature of the home as well as the deterioration, the client’s home health aide refused to return to work for Mrs. B. At the same time, Mrs. B was diagnosed for the first time with diabetes and Allen requested a nurse be assigned to the client. On June 13, Patti O’Neill, RN, visited Mrs. B and found her dehydrated, a blood sugar of over 300 and very low blood pressure. She reported a stack of toilet paper smeared with feces 4 feet high in the bathroom, as well as raw sewage in the client’s basement and she called 911.

At this point, Mrs. B’s risk had increased to the point that successful intervention in the court system was possible. Mrs. B was transferred to a private-pay bed in an assisted living, with the promise that with the sale of her home, her bill would be paid. He used emergency funds to purchase clothing for the Mrs. B, met with two of the client’s estranged children, explaining how the county had tried to meet client’s wishes to remain in her home for many years but why guardianship was necessary at this time. He assessed that neither child was an appropriate guardian, presented Mrs. B’s situation at guardianship panel, discussed the client with the guardian ad litem appointed by the court, testified in court, and oriented the volunteer guardian to the client and her family.

Adult Services social work supervisor negotiated with a for-profit assisted living to allow admission but defer payment until her home, worth $500,000, could be sold. They agreed to do so.

Presently, after eight months in an assisted living , Mrs. B’s medical conditions have improved. Her home has been sold, after an engineering report showed that the support beam under the living room was almost completely eaten away by termites. She is in a private room, is offered and attends events outside the facility, her diet is greatly improved as is her daily hygiene. Staff report she enjoys activities. Despite all the improvements, the client remains angry with Allen and refuses to work with him further.

Although her illness prevents her from having insight into the risks to her life, it is clear Allen and all staff from ADSD who worked with this client did the right thing the right way for this client at the right time for this client.

Supervisors - How to Celebrate and Communicate Frontline Workers Successes - Story Three

Two homeless clients at one time!

Adult Services Social Worker Sonny Rogers had not one but two clients who experienced sudden homeless within two days of each other. One of his clients, Mr. T, an 81-year-old frail gentleman, refused to do any advanced planning concerning an imminent eviction.

Days before Mr. T was evicted, another of Sonny’s client’s, Mrs. H, a 74-year-old frail female, suffered the sudden death of her friend and roommate of over 15 years. Mrs. H had been dependent on this friend to make most decisions in her life and she was at a loss as to how to manage without her.

Within days of each other, Sonny had two homeless clients, neither of whom had any family to assist.

Over the next two weeks Sonny was able to negotiate with a local HUD senior building staff to find them apartments, obtain the funding (security deposits, first month’s rent) for both of them, fill out all necessary paperwork and forms for the moves, bring both clients to their potential apartments multiple times, hire movers, be present for the moves, and ensure both clients received the necessary on-going support (Home Health Aide assistance, personal advocates, meals program, visiting county nurse).

While this alone is quite unusual – working with two homeless clients simultaneously – what makes Sonny a stand out social worker is the manner in which he conducted himself. He was being pressured by multiple sources both within and outside his organization to move more quickly and “make the moves happen.” He refused to be influenced by these pressures and instead understood and respected each client’s need to move at a pace of their own choosing. His demeanor during this time was as calm and centered as when he is under less pressure.

Sonny is an important and talented member of the adult services team who performed very well under difficult circumstances.

Supervisors - How to Celebrate and Communicate Frontline Worker Successes - Story Four

Seventeen Years of Service

Sixty-seven-year-old Ms. J was referred to Over Sixty Intake January, 1990 by her skilled home health nurse. Ms. J was recovering from a compression fracture of her lumbar spine and was depressed because, due to this injury, she was forced to abruptly withdraw from the work force. She requested and received a companion a few hours a week to help with laundry and do light housekeeping, as well as an on-going social worker as she had few family supports.

As the years passed, she required increases in companion services due to interrelated medical problems including Cardiopulmonary Disease, Osteoporosis, Glaucoma, and Diabetes, as well as multiple compression fractures. She received liquid nutrition, a visiting nurse from nursing case management, a human services aide to bathe her, home-visiting doctor, assisted transportation, meals on wheels, Section 8, an electric scooter, a power of attorney, Sheriff’s office daily check-in call (SOS volunteer), and senior adult mental health as her medical and emotional condition declined.

She worked with four different social workers and then was assigned to Adult Services social worker Sehwha Rha in 2004. At this point, she had been in and out of the hospital and nursing homes multiple times, each time insisting on returning home, as she found the hospital and nursing home environments to significantly reduce her quality of life and restrict her freedom of choice.

As the number of volunteers and professionals serving this client increased, each brought with them their unique concern for client’s safety. Ms. J was at this time bedridden and needed nursing home level of care. She was screened and was receiving Community Based Care services through Medicaid, however this service did not cover her at night. She was also exhibiting signs of dementia and paranoia.

Sehwha Rha’s primary clinical function with this client became to help the various volunteers and providers express and process their concerns for the level of risk that remained in this client’s situation. Ms. J was being left alone at night and did suffer from Sun-downing dementia. However, it was felt that her risk was minimized as much as possible while respecting the client’s persistent wish to be care for and to die at home. This risk was reduced due to the excellent services of the Medicaid CBC aide, the SOS volunteer, nursing case management, and Sehwha Rha.

Sehwha was able to educate all involved of the client’s 17-year-long wish to remain at home until death and to be a sounding board for all the anxiety that each volunteer and service provider felt about their own liability and client’s real risk. If any one of these volunteers had not felt comfortable with Sehwha’s role as the primary co-ordinator and not open to discussing their feelings with Sehwha, they could have made the choice to initiate and push for guardianship and placement, which would have served to reduce their own anxiety about their own liability. But this would have been in opposition to the client’s long-standing wishes to remain outside an institution until death.

Ms. J died in May, 2007, at the age of 86, never having been institutionalized.

The Need for Multidisciplinary Teams

- Two of many organizations with well-researched and long-standing Multidisciplinary Teams include Illinois and the San Francisco Consortium for Elder Abuse Prevention. If you are interested in their books defining the roles of team members as well as how teams may wish to function, please post a request for this material by navigating to the top of this site and click "new post."

- Empowered adult services social workers have a sense of team effort – that they are not on their own when wrestling with difficult clinical decisions.

- Assessment of adults requires social workers to be familiar with many different domains of functioning, but social workers are not equally expert or comfortable in all areas. Multidimensional assessments may at times require the participation of a multidisciplinary team. Depending on the client’s presenting problem, team members can include mental health specialists, physicians, nurses, psychologists, code enforcement, attorneys, religious leaders, etc.

- Participation in teams by Adult Services/APS social workers and supervisors benefits clients. Teams may include standing interdisciplinary teams for case staffings and care planning and preguardianship panels. Empowered Adult Services/APS social workers have a sense of team effort – that they are not on their own when wrestling with difficult clinical decisions. Assessment of adults requires social workers to be familiar many different domains of functioning, but social workers are not equally expert or comfortable in all areas.

- Multidimensional assessments may at times require the participation of a multidisciplinary team. Depending upon the client’s presenting problem, team members can include mental health specialists, physicians, nurses, psychologists, code enforcement, attorneys, religious leaders, etc. The multidisciplinary team may require a written case staffing to be completed and presented. As Virginia Code does not provide for Adult Services/APS multidisciplinary teams, clients whose case situations are being discussed should sign releases of information. Not using the client’s name does not preclude the release of information as team members will likely be able to identify the person based upon the descriptive information.

- A preguardianship panel, composed of representatives from legal services, the Community Services Board, the Area Agency on Aging, and a consumer group(s), provides objective review of case situations where APS is considering appointment of a guardian/committee. A preguardianship panel may have standing monthly meetings. For the meeting, Adult Services/APS social workers present written summaries of case issues, mental incapacity descriptions, support systems, less restrictive alternatives considered, and areas of risk. Written material is collected at the end of the meetings. Records of the meeting are retained and include the recommendations of the panel. Only cases which receive the concurrence of the panel are forwarded to the county/city attorney.

- Reasons (Wolf and Pillemer, 1994) cited for taking a client to a multidisciplinary team or having a team meeting were:

- 1) To clarify the individual agency roles

- 2) To receive help in handling a case

- 3) To seek solutions to cases that defied resolution

- 4) To resolve disagreements with other agencies regarding aspects of the case

- 5) To obtain legal and medical consultation not readily available to workers through other means

- When running these team meetings ground rules should be set. Some suggestions:

- 1) Confidentiality – what is said in the room stays in the room, except when expressly stated as an exception;

- 2) No one person should dominate the conversation;

- 3) No attacks – assume goodwill, do not expect perfection;

- 4) It is OK to admit one doesn’t know something or show mistakes;

- 5) Every member should recognize the different skills that team members bring to the task

- 6) Communicate clearly without unnecessary professional jargon or acronyms

- To function as a team they must clarify their separate roles and share both information and their separate professional judgments. For example, there will be no team if the nurse does not understand and respect the unique contribution of the social worker to the client’s well-being and vice versa.

On-going Training, Mentoring, Professional Associations to Consider

- A new frontline worker or new supervisor to Adult Services in particular may wish to identify for him or herself a mentor. This mentor should be someone you respect and who understands the richness and complexity of doing community-based case management with adults. This person need not be in your agency or even in your county. This website and the message board on it is meant to assist in this area but communicating by phone, computer or face to face with a mentor has been shown to be very helpful in creating excellence in practice.

- Also, the partnership the state DSS has with Virginia Commonwealth University has been mentioned in nationwide research as a model of excellence in regards to on-going training. VISSTA offers excellent classes and is responsive to the needs of AS workers and supervisors.

- There are trainings outside the VISSTA courses which offer networking as well as training opportunities.

- Finally, consider joining professional associations such as: VASWP, VGA, VCPEH, VLSWP, NCAA

Record Keeping - Clinical Importance Beyond Data-Gathering

- What are the purposes of case records and what constitutes good record keeping?

- Most adult services social workers and managers agree that their practice should be accountable and that this accountability is primarily reflected in clients’ records. The phrase “not written, not done,” underscores the importance of the written word for documenting interventions, capturing clients’ and social workers’ successes, and identifying areas for additional work.

- Much of the literature on record keeping for social work describes methods designed for settings that provide office-based therapy.

- The job of public services social workers, however, is substantially unlike that of social workers who perform therapy. Many of the reasons clients come to adult services agencies is that they are experiencing some difficulty in interacting with their environment that is often exacerbated by the lack of financial means to resolve the problem independently. Their needs may produce emotional discomfort or a total inability to cope with the problems that beset them, but the principal goals of interventions will first be to improve clients’ functioning by helping them find ways to meet material needs, and second, to modify behaviors.

- Public services social workers act as gatekeepers for many of the assistance problems funded by local tax dollars, by not-for-profits, or by the state or federal government. Record keeping in public agencies has been seen foremost as a matter of documenting the execution of a public trust, often involving the disbursement of substantial sums of money.

- There are two reasons for social workers to write client notes/narratives/dictation as well as complete service plans:

- 1) Using a good record-keeping format can prompt workers to gather information in a more holistic, directed manner and reflect as they write up their notes on what the information means.

- 2) It provides a concise way to communicate with others who may be involved in the case or with colleagues who may need to assist the client when the principal social worker is not available.

- Good records provide a concise, usable account of:

- 1. Why the client came to the agency;

- 2. What the presenting problem was

- 3. What goals were developed?

- 4. What interventions were planned and implemented?

- 5. How the interventions worked for the client

- 6. What is being worked on presently?

- Notes should be tools that demonstrate social workers’ reflective thinking and professional judgment

- Notes should capture important information and decisions clearly in as little space as possible and with a minimum of burden to social worker

- Provide case continuity and give other workers a historical context for chronic problems

- For supervisors paperwork should provide a basis for:

- Supervising appropriate practice steps and interventions

- Identifying skills and competencies needed by social workers

- Evaluating the effectiveness of adult services practice (including quality and timeliness) and programs

- Providing social workers with a method of recording that parallels practice will enable them to work more efficiently with greater clarity of thought.

- It will provide a mandatory time for necessary reflection in a constantly reactive, on-the-go environment.

- Because clients, and potentially the legal system, have access to case records, anything a social worker writes about clients should reflect respect for and sensitivity to them. Similarly, any statement about a client’s condition should include the basis on which it is made.

- In a practical sense, whatever is not documented did not happen, and this can have legal repercussions that may affect the supervisor and the worker.

- Records are only as good as the information they contain. Records that focus on documenting outcomes for clients reflect a commitment to their well-being

- Automated record keeping and date gathering can be a powerful tool in the hands of the direct practitioner and the agency’s managers. Nonetheless, for the greatest likelihood of success and acceptance, plans to introduce data-gathering systems in the workplace must first focus on direct benefits to clients and practitioners in their day-to-day interactions and secondarily on their potential for gathering data for program evaluation and development.

- Supervisors may wish to review their use of electronic records to balance efficiency in the workplace with the need for client confidentiality.

- Supervisors may wish to periodically purge their systems and destroy files after a certain period of time, as determined by their local agency policy. Five years is often given as the most common number of years a record is retained.

Evaluations

- Historically, few adult services programs conduct any ongoing evaluation of client and family outcomes. Most information systems focus on process evaluation: how many APS cases were investigated, how much in-home services were provided. They seldom are designed to capture on an ongoing basis such things as:

- Whether the burden on family caregivers is reduced as a result of a particular service intervention

- Whether the worker increased access to quality medical care, resulting in slower functional loss for clients (for example, managing the removal of cataracts so client does not go blind and need more services) and fewer hospital visits

- Whether the AS worker has prevented homelessness

- Whether the service has improved the quality of the client’s life by lessening anxiety; lifting depression

- Agencies should consider evaluating these quality of life measures in addition to basic numbers of clients served, as what gets measured receives attention and, ultimately, priority.

Other Available Assessment Tools

- If you post a request on this site, the following forms may be e-mailed or mailed to you:

- Values Clarification: Values History Form

- Ethnicity: Cultural Assessment Tool; Multidimensional Helath Locus of Control Scales

- Environment: OARS comfort in environment

- Economics: Economic Resources Assessment of the OARS

- Social Supports: Family and Friends APGAR

- For Falls: Tinetti Balance and Gait Evaluation

- For ADLs and IADLs: OARS, KATZ, Direct Assessment of Functional Status, Physical Data Visual Evaluation, Barthel's Index

- Alcoholism: Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test, Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test, CAGE Alcoholism Screening Test

- Safety Checklist for Imparied Individuals/Fire Safety Checklis

- Tool to distinguish dementia from depression

- Dementia: Trail Making Test - for dementia, Global Deterioration Scale, Clinical Scale for the Staging of Dementia, Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist, Functional Rating Scale for the Symptoms of Dementia, Short Blessed Test for Dementia

- Does client need to go to a nursing home?: Algorithm for Deciding need for Long-Term Care

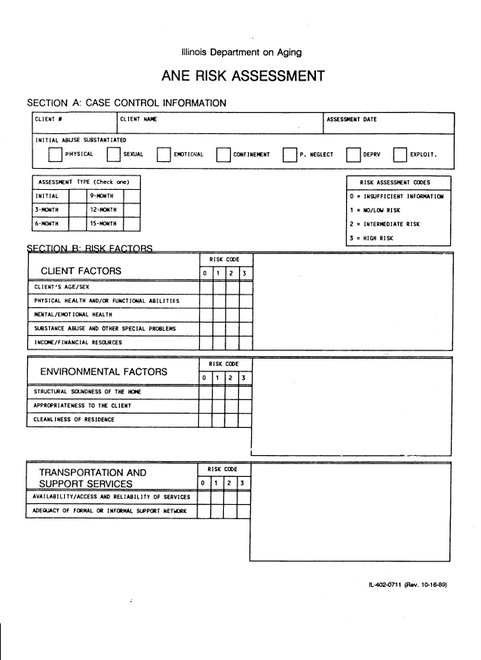

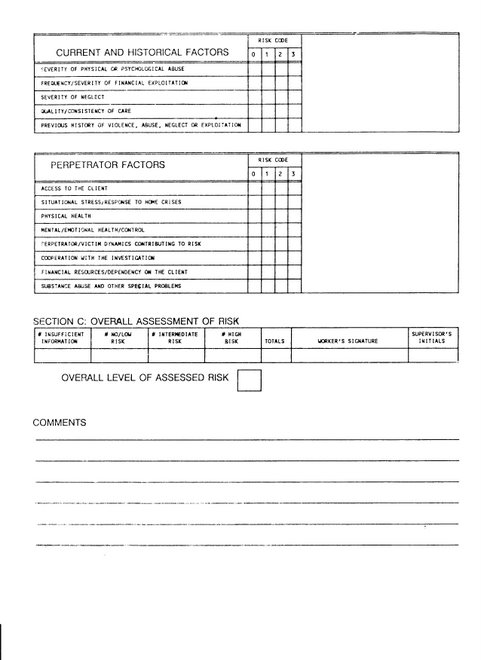

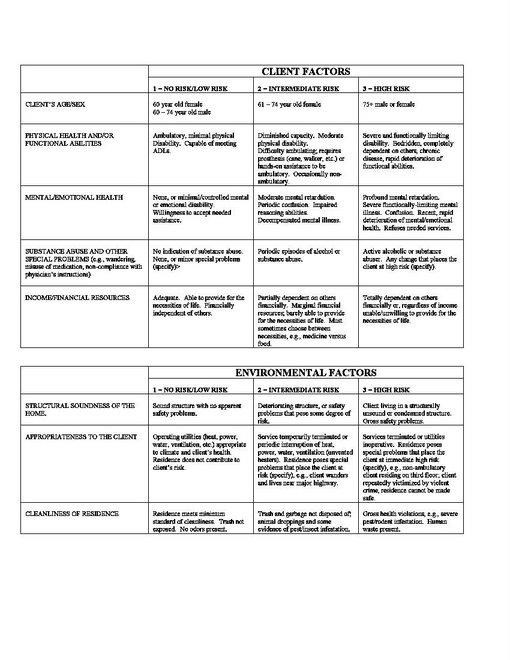

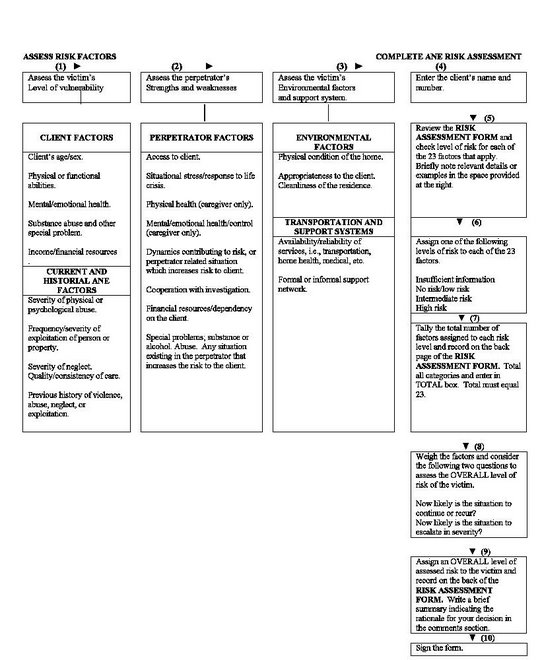

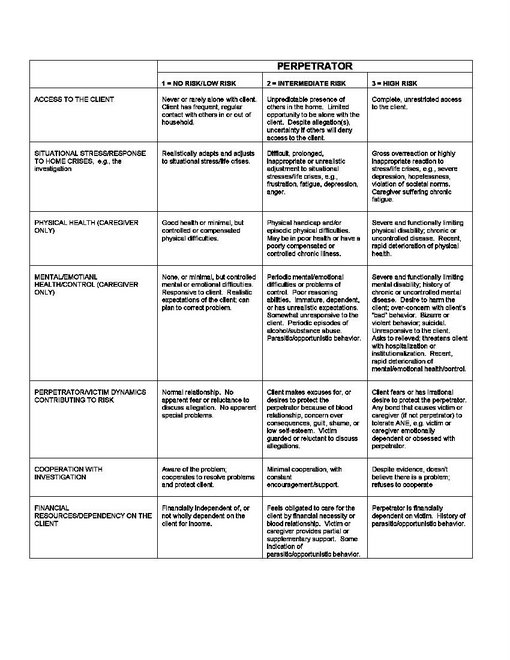

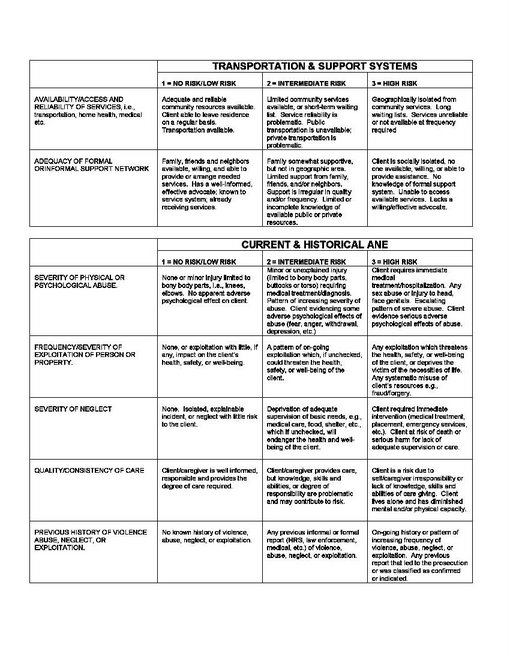

Tools Other States Use - Illinois Risk Assessment Page 1 of 2

Tools Other States Use - Illinois Risk Assessment Page 2 0f 2

Risk Assessment Tool - Illinois

Risk Assessment Tool Illinois

Illinois Assessment Page 4

Illinois Assessment - Page 3

Research Books and Articles Used to Develop this Site

- Social Work Practice with the Frail Elderly and Their Families: The Auxiliary Function Model (1983) Barbara Silverstone, DSW Executive Director of The Benjamin Rose Institute in Cleveland, Ohio and Ann Burack-Weiss, MSSW Training Consultant Brookdale Institute on Aging and Adult Human Development Columbia University School of Social Work.

- The Field of Adult Services: Social Work Practice and Administration (1995) Gary Nelson, Ann Eller, Dennis Streets, Margaret Morse, editors. The adult services programs throughout North Carolina were a central source of expertise and experience in the writing of this book; in addition, state social services agencies and schools of social work around the country were contacted and asked to share information – responders included Virginia, Massachusetts, New York and. See attached for more information on the editors.

- As well as the article: “Clinical Aspects of Case Management with the Elderly” (1994) Harriet Hailparn Soares, LCSW and Madeleine Kornfein Rose, DSW, LCSW, practitioner and professors in Long Beach California.

- Managing Manipulative Behavior in the Helping Relationship by Dean H. Hepworth (1993), Social Work.

Links to Helpful Websites

- Adult Services and Adult Protective Services Manual

- Alzheimer's Association

- Area Agencies on Aging

- Better Business Bureau

- Children of Aging Parents

- Demographics, property data for US cities and towns

- Department for the Aging - Virginia

- Eldercare Locator Service

- ElderLiving Source - Comprehensive directory of Assisted Living

- http://www.elderabusecenter.org/

- Medlineplus - Information on thousands of prescription and OTC medicines

- Nation's largest Elder Abuse archive of published research, training resources, government documents

- National Center on Elder Abuse

- National Citizens' Coalition for Nursing Home Reform

- National Institute of Mental Health

- National Institute on Aging

- Nursing Home Abuse

- Partnership for Prescription Assistance - 275 public and private patient assistance programs

- Reliable drug information side effects and drug interaction

- Senior Navigator

- US Veterans Affairs Department

- Virginia Alliance of Social Work Practitioners

- Virginia Department of Social Services/Adult Protective Services

- Virginia Health Information

- Virginia's Judicial System